GPU-accelerated model checking

Bringing GPU acceleration to statistical model checking.

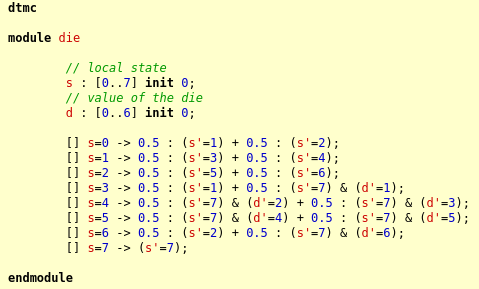

PRISM is a state-of-the-art and well-known probabilistic model checker. The core idea of model checking is to describe a complex system with an abstract mathematical model, define its properties in a formal logic language, and verify the properties automatically. PRISM uses probabilistic models such as discrete-time and continuous-time Markov chains (DTMC, CTMC), Markov decision process (MDP), and probabilistic timed automata (PTA).

The classical approach of PMC is to use the linear algebra methods, such as represent the model and properties as a system of linear equations and solve them in an iterative fashion. While this method has been applied successfully in many cases, it does suffer from the well-known problem of state space explosion. Furthermore, a wrong selection of termination conditions might lead to incorrect results, as we will show later.

Another approach is to analyze the properties statistically: use the Monte Carlo method to generate many random walks through the model and average the results of property verification. It’s not a perfect method, the number of samples limits its precision, and it cannot easily verify some qualitative properties. Nevertheless, a model checker will benefit from a fast and easy-to-use statistical simulator.

The example presented above is a DTMC model written in the PRISM language (see PRISM website for full discussion). It simulates throwing a 6-side dice by using only coin throw with 50% probability. In the end, reaching each value of d has exactly one chance in 6. The state of the model is a composition of all variables, and the commands describe transitions. Each transition includes a guard specifying when this transition can be taken, followed by the multiple possible transition results with corresponding probability rates.

Finally, the transitions can be synchronized, and PRISM models can include multiple modules that are executed in parallel. If we have many models with a huge number of possible states in each of them, we will end up with the state space explosion problem - there are too many states to handle when computing a solution.

Clearly, this model is not very difficult to simulate - we need to encode transition guards as if conditions, compute the probability distribution of all available transitions, and randomize the selection while verifying properties in each step. Unfortunately, PRISM includes only a limited simulator that is quite sequential and implemented entirely in Java, reinterpreting the model above in every transition. The simulator is sufficient for debugging purposes, but it’s not fast enough for statistical computations.

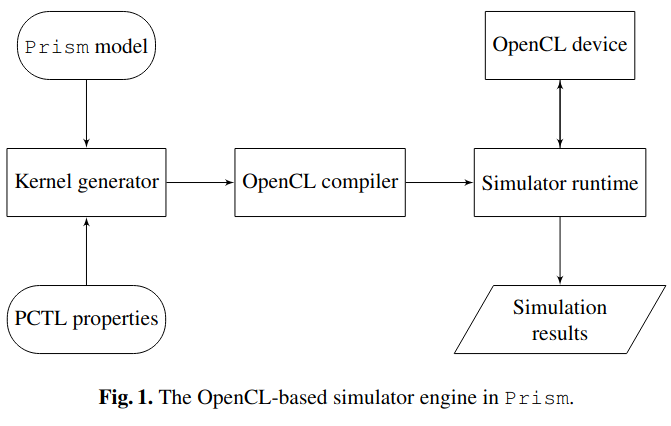

We created prism-faststim, an OpenCL-based fast and heterogeneous simulator for PRISM. We created a high-level Java library for the generation of OpenCL kernels, and we used it to build a just-in-time source-to-source translation of the PRISM model and properties to a dedicated compute kernel. The kernel is a program executing the model on many GPU and CPU threads, using the single-instruction-multiple-data paradigm. The implementation had to be specially adapted for GPU devices, leading to low-level optimizations. For example, when simulating independent paths, they will diverge at some point which is not ideal on a GPU device with limited ability to handle diverging control flow. We compress variables sizes as much as possible to save the register and local memory space. We want to perform synchronized transitions in a single step to keep for performance reasons, but this might require multiple copies of the state vector because of Read-After-Write race conditions. To keep the high efficiency and decrease memory consumption, we use a single copy of the vector and analyze transitions to detect variables affected by a race condition and make copies of only those memory locations.

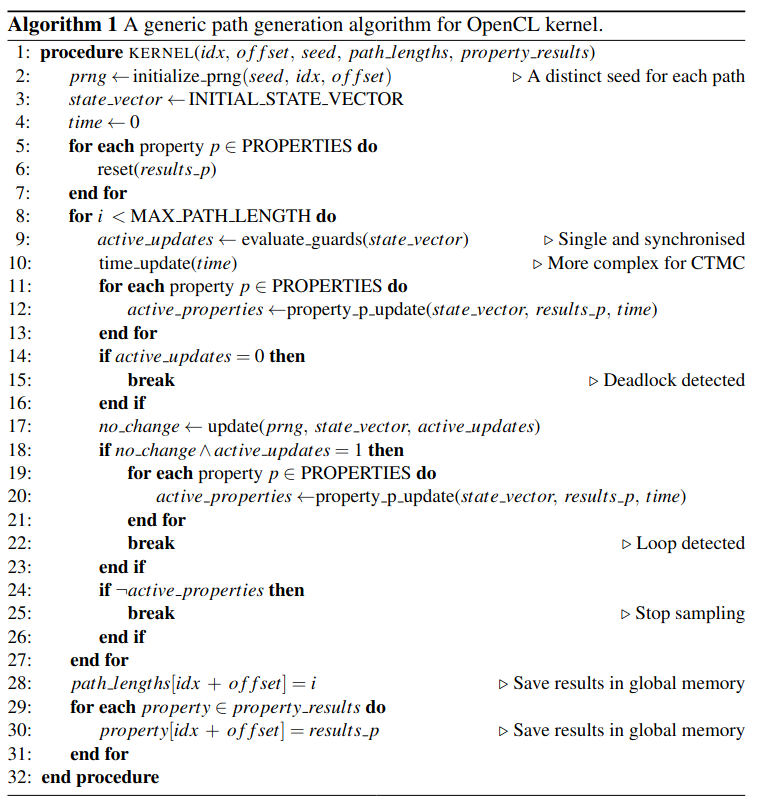

The simulation algorithm presents a single OpenCL thread executing a single path through the model. The second loop (lines 8-27) generates the path until any of the following happens: its maximum length is reached (line 8), a deadlock (line 14) or a self-loop (line 18) occurs, or all properties are verified precisely enough (line 24). The last loop (lines 29–31) copies the collected data into the global memory, which will be collected later by the host simulator.

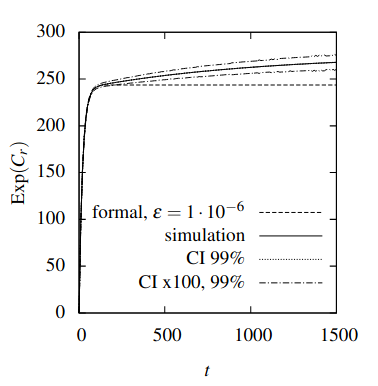

We demonstrated the usability of our tool on an example of computing an instantaneous reward in a CTMC. PRISM performs discretization and performs an iterative process to approximate the probabilities. When executing that operation, Prism also tests if a steady state has been reached by checking the difference between elements in solution vectors from two successive steps. If the difference is smaller than a constant threshold, the process is terminated early as such a state has been reached. However, in some models, detecting a steady state is premature if the default termination criterion is used. This can lead to incorrect results (plot above, on the left). Therefore, the fast statistical model checking is used to verify with a high degree of certainty if the analytical result is correct, helping users discover incorrect results.

Furthermore, we compared the performance of our simulator on an AMD R9 Nano, a modern mid-range GPU with 4096 stream processors, and on two Intel Xeon E5-2630 v3 CPUs with clock frequency 2.40GHz, each of them providing eight cores with HyperThreading, resulting in 32 threads for OpenCL. The results (plot above, right) show that two CPUs are several times slower than a GPU. This shows the advantage of streams processors in the case of a large number of parallel tasks.

The results from the PRISM simulator are not shown on the plot, as it is not optimized for speed. At t = 2000, where long paths make it especially advantageous to use the on-the-fly compilation, it took the PRISM simulator over 130 minutes to evaluate the same reward property on the same CPU, thousands of times slower comparing a respective simulation on a GPU.

This work is a result of my Bachelor’s thesis conducted at the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Informatics, Polish Academy of Sciences, under the supervision of Dr. Artur Rataj, Dr. Mateusz Nowak, and Prof. Tadeusz Czachórski. We presented the paper at the 25th International Workshop on Concurrency, Specification and Programming.